When George Ouma made the decision to organize an exhibition showcasing vinyl music records at the Goethe Institut, he had no idea how much interest it would generate among millennials.

“Young university students would walk in and simply stare at the record covers,” he explains.

“Some of them have never even seen a vinyl record before and mistake them for oversized CDs. Even their parents may not have had much exposure to records and turntables.”

Ouma, who is in his early 60s, belongs to a generation that grew up with vinyl record players, which were the primary source of entertainment during that era.

This generation witnessed the rise and fall of cassette tapes, the advent of compact discs (CDs) followed by their decline, and the limited success of MP3 players against the ubiquity of smartphones.

During that era, playing and listening to music was a ritual. And this ritual couldn’t be rushed. First, you delicately removed the vinyl record from its sleeve, carefully examining the cover design while contemplating the lyrics.

After gently lifting the lid of the player, making sure it was still attached, you carefully placed the record on the turntable and skillfully positioned the stylus, mindful of not scratching the precious vinyl. There would be a crackling sound before the music burst forth, transporting listeners to a tranquil world. The experience would be repeated on the other side of the record.

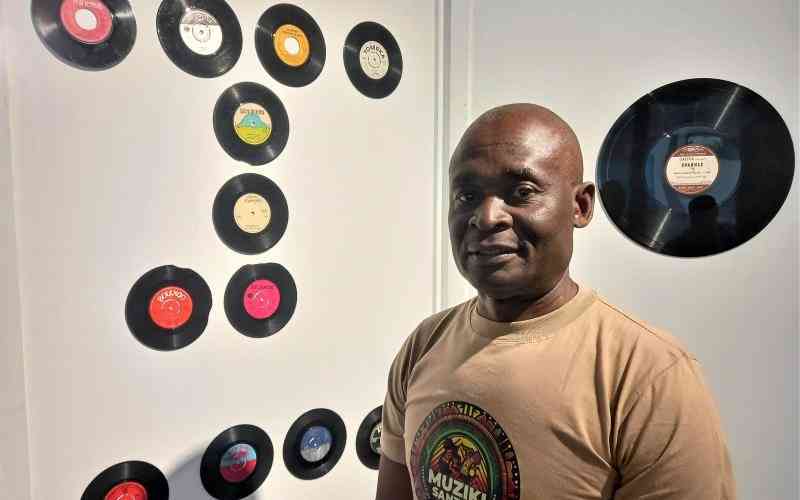

Through his exhibition, called Muziki Santuri, which opened on February 17 and will conclude next week, visitors are not only treated to these experiences, but also offered insights into the history behind the cover designs, showcased murals of iconic Afropop musicians, antique gramophone machines, jukeboxes, documentaries about vinyl records, and talks about the rich musical heritage of a bygone era.

Born in Ng’iya, Siaya County 62 years ago, Ouma began his record collection in 1978 when he joined his uncle’s music shop in Kisumu. The two were the primary distributors of PolyGram records in western Kenya, with satellite stations in Busia and Migori.

“Before placing an order for certain music from PolyGram, I would receive a free record as a sample. I kept some and gave away others. The remaining records were left in Kisumu when I moved to Nairobi in search of better opportunities,” he recalls.

In 2000, Ouma had a chance encounter with a friend of Tabu Osusa, a renowned music producer and the founder of Ketebul Music, who had visited from England. This friend took notice of Ouma’s collection of vinyl records, which he regularly showcased on his social media pages.

“He told me, ‘George, vinyl records are making a comeback in Europe. People out there have a deep appreciation for Kenyan music, so if you have any records, keep them safe for future use,'” Ouma recalls. “That got me thinking about the records I had given away to friends, and I started devising ways to reclaim some of them.”

Unfortunately, some of Ouma’s friends had already discarded the records, while others managed to salvage a few from their own personal archives. Ouma gathered whatever records he could from these friends, along with the ones he still had in his possession, and headed to Nairobi’s River Road, the heart of Kenya’s Benga music scene, to acquire more.

In 2005, a group of music enthusiasts from Germany sought Ouma’s advice on recording traditional musicians in the village. Initially, they had intended to work with Tabu Osusa as their main contact, but Osusa directed them to Ouma instead.

Ouma was instructed to establish a contractual arrangement with the director of the Goethe Institut before proceeding to the village to record with local artists. The group returned a year later for further recording sessions.

However, Ouma felt dissatisfied with these recordings as he believed he was exploiting the local musicians, who received little in return for their contributions.

“I wanted the recordings to take place in Europe, where the local group could perform live,” he explains. “My proposal was accepted, and my people from Siaya were booked for several tours between 2013 and 2015. We performed gigs for consecutive months. Finally, the local artists were content.”

Prior to another trip, a booking agency manager requested that Ouma bring along some vinyl recordings to play for a fee. One of these gigs earned him close to Sh200,000, which he used to purchase more vinyl records from the Kenyan market. Presently, Ouma’s collection comprises nearly 10,000 vinyl records.

During a visit to the Netherlands, he came across a vinyl record exhibition, sparking the idea of hosting a similar event in Kenya.

Upon returning home, Ouma approached Alliance Française through his Jojo Records, but received no response. Eventually, he managed to convince the Goethe Institut to host the exhibition, attracting hundreds of visitors daily.

Like others from his generation, the mere sight of these records and their resurgence in different parts of the world fills Ouma with nostalgia.

He reminisces about the past, recalling how, as a young man in his village, he would play records at what they called “tea parties” for Form Four graduates. Ouma even used the same tactic to woo his wife, noting that any young man without a record player faced challenges in the dating scene.

“If a young man who did not own a record player wanted to attract the attention of a young lady, he had to borrow a player from a friend and only when the girl ‘got into the box’ would the boy return both the machine and the records. Sometimes he would return the items after the two became man and wife. The only key expense used to be the dry cell batteries. A small fundraiser would sort out the problem,” says Ouma.

Today, thanks to the proliferation of digital devices, music can reach wider audiences quickly. But these methods have their drawbacks too since music can be pirated and distributed without any benefits to composers and distributors.

“You could not pirate music in the vinyl records and happily, the records have in recent times sold more copies than CDs in some parts of Europe. We hope investors can come in with a vinyl press which will be a great achievement for Kenyan musicians,” he says.